In the 1920s and 1930s, if you lived in Franklin County, most likely you were in involved in the county's biggest industry — making illegal whiskey or moonshine. The proliferation of stills prompted then-Deputy Prohibition Commissioner N.C. Alexander to note that of the 30,000 people living in Franklin County at the time, 29,999 were "mixed up directly or indirectly in the whiskey business."

Franklin County was known during Prohibition as "the wettest county in America."

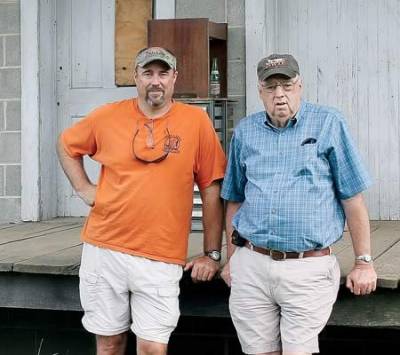

Eighty years later, the grandson of one Franklin County's moonshiners, Robert Bondurant of Chase City, is carrying on the family legacy by making moonshine in a still pot handed down through the family. That's where Robert's ties to the past ends.

He has had to forego using the family recipe, since it died with his grandfather and great uncles. And he won't be making his whiskey in Franklin County. Instead, he's setting up shop in an old warehouse on Third Street, across from the Southside Roller Mill in Chase City.

On a recent Sunday afternoon, as Bondurant surveys the building that is about to become his distillery and gift shop in Chase City, he asked, "Do you know the difference between a distiller and a moonshiner? I'm a distiller. I pay taxes." He is also licensed by both the federal government and the state of Virginia to operate a distillery, which, of course, was not true of his grandfather and great uncles' stills.

For Bondurant, his new venture is as much about making moonshine as it is about telling what he calls "the real story" of his family's moonshine past.

For Bondurant, his new venture is as much about making moonshine as it is about telling what he calls "the real story" of his family's moonshine past.

He makes no apologies or excuses for the criminal side, but claims the book written by his cousin Matt Bondurant, "The Wettest County in the World" — which was made into a 2012 movie, "Lawless" — is more fiction than fact.

Robert Bondurant is the grandson of Jack Bondurant, who with brothers Forrest and Howard operated one of the many stills dotting the countryside of western Virginia. By 1935, the brothers were also unindicted co-conspirators and central figures in one of the most sensational and longest trials in the history of Virginia, "The Great Moonshine Conspiracy Trial."

On Feb. 7, 1935, a grand jury meeting in Harrisonburg handed down a 22 page indictment against 34 individuals and one corporation, and named another 55 unindicted co-conspirators who allegedly were engaged "in carrying on the business of a distiller" without paying tax on the distilled spirits. Those indicted included Franklin County Commonwealth's Attorney Charles Carter Lee (the great nephew of Robert E. Lee), plus a former county sheriff, four deputies and a federal revenue agent.

Following the indictments, The Roanoke Times reported that Lee and the five other officials were accused of accepting money for protection of those engaged in illicit whiskey operations.

When the trial ended, the moonshiners had either pled guilty in exchange for light sentences or were found guilty of conspiracy. Two deputies were dead, one from pneumonia and another allegedly shot while transporting a prisoner. The former sheriff and a deputy, Abshire, were convicted of conspiracy, but Carter Lee was found not guilty. Later, eleven of the twelve jurors signed affidavits accusing Carter Lee of jury tampering. They claimed he somehow influenced the decision of the twelfth juror.

Jack, Forrest and Howard Bondurant, like many of the farmers living in the hills of western Virginia, turned to moonshining as a way to sustain their family during the Great Depression. Robert's father, who is also named Jack Bondurant, said his father spoke very little about his life as a moonshiner. The children were not allowed at or near the still. To the family, Jack Bondurant was a farmer. He never tried to bring his children into the moonshine business.

Both Robert and his father Jack are retired game wardens.

Jack recalls when he first realized what his father was doing to earn a living, "I was a very inquisitive kid, so I probably realized what my father did, when I was 9 or 10." He also has memories of his father being away from home — among them three brief periods when the elder Jack Bondurant was sentenced to prison because of his moonshine operation.

One of Jack's more vivid memories involves the shooting of his father and Uncle Forrest by a local sheriff's deputy. Jack stressed that he was not present at the shooting, which took place on a bridge at Maggodee Creek in Franklin County. His version is what was told to him after the fact and what he gleaned from the grand jury testimony of his Uncle Forrest and father as written in the T. Keister Greer book "The Great Moonshine Conspiracy Trial of 1935."

In Jack's account, his father and uncles, who began producing moonshine in 1928, paid Franklin County Deputy Sheriff Henry Abshire between $25 and $30 each month to keep state and federal revenue agents away from their stills. The first time they attempted to haul liquor — the phrase used to describe the transportation of the liquor from the still to a buyer — Jack and Forrest were shot, after refusing to pay additional protection money in the form of a carload of moonshine.

According to Jack and Robert, the elder Jack and Forrest were each driving a vehicle filled with moonshine when they were stopped by Abshire and Deputy Charlie Rakes at the Maggodee Creek Bridge. The deputies demanded they turn over one of the two cars. Despite Forrest's protest reminding Abshire that payment was already made to him, the deputies persist. Hoping to stop them from seizing the moonshine, Jack is said to have removed the keys from one of the vehicles and to have tossed them down the bank toward the creek. Rakes responds by shooting Jack.

Robert says it is his understanding that the bullet entered his grandfather's side under one arm and exited out the other side of his body under the opposite arm. When Forrest rushed to his brother's aid, Rakes shot him in the stomach. "Forrest nearly died from his wounds," Robert says.

By this time, the third brother, Howard, has arrived at the Maggodee Creek Bridge. He takes Jack to the hospital in Rocky Mount, and Abshire drives the wounded Forrest into town where they meet with Lee. Abshire arranges, with the help of Lee, to have the remaining vehicle towed to Rocky Mount.

The family lore, according to Robert, is that when the car seized by the deputies was stopped at the bridge, there were over 120 gallons of moonshine inside. By the time the car reaches town, supposedly less than 30 gallons remained.

Both Jack and Robert say that Lee, was the mastermind behind the moonshine operation. They also refute allegations made in the book and the movie "Lawless" that there were any connections between the Franklin County moonshine operation and the Chicago mob.

Eventually, Franklin County's moonshine operation drew the attention of federal officials. In part, because of the quantities of sugar, malt, hops, corn meal and yeast that poured into a county with a population of 24,000. Records introduced during the Great Moonshine Conspiracy trial, list shipments of nearly 34 million pounds of sugar, 13 million pounds of corn meal, 1 million pounds of malt, 30,300 pounds of hops and 35 tons of yeast making their way to Franklin County during a five-year period.

Robert said, "That's more sugar than they ate in New York City."

It was estimated that had the still operators paid taxes, their moonshine sales would have generated $5.5 million in excise taxes at the 1920 rate. Today, that is equal to $95.6 million.

Robert says the "best part of the story" about the Great Moonshine Conspiracy really takes place during and after the trial. To learn that, people will have to come to his distillery after it opens in early 2015.

He plans for the distillery to be a living history lesson that includes the manufacture of a "prohibition style beverage" using the prohibition style processes. "When you enter the place, I want you to feel like you have stepped back in time."

Unfortunately, his grandfather's still and recipes are long gone. The elder Jack Bondurant spent his later years farming, and building houses.

Through research, Robert said he developed a recipe and process that will replicate that western Virginia prohibition era moonshine. When he first opens, Robert said he will not be able to serve or sell any of his product on site. For that, he has to apply for a different set of permits. Still, he hopes people stop by for the history lesson.